There is a long list of benefits that come from spending time in nature.

You know it.

I know it.

We all know it.

There’s plenty of quantifiable scientific evidence demonstrating these benefits including: increased longevity, physical health, positive thoughts and reduced stress.

It makes sense that nature is also place where our creativity thrives and our capacity to focus and problem solve is restored.

According to Attention Restoration Theory, this is exactly what happens.

When we spend time concentrating, focusing on specific problems or trying to get results out of our thinking, our brains grow fatigued.

When we are mentally fatigued our cognitive ability to ideate, imagine, and think laterally, discern, choose, plan, is reduced.

This is especially true during the phase of creativity we label the incubation period.

When we are waiting for ideas to pop into the ‘aha’ realm and become suitable ideas.

In nature, or while looking at nature – even photos it seems – our attention is free to wander without the brain having to make too much effort.

We are biophilic beings.

We love nature and all things nature. That’s one reason most of us feel GOOD in nature.

But there are four elements that are present in nature, especially in wilderness and more unfamiliar natural settings that contribute to this restorative potential:

1. Fascination – this is apparently, the most important factor. You would have experienced it.

It’s the way our brain’s focus naturally goes towards natural features that catch our attention – waterfalls, streams, wildflowers, clouds, sunsets, mountains peaks, the ocean.

The lack of effort needed to pay attention in nature; the way our brains take it all in effortlessly, helps our brain to relax and restore its capacity to focus and problem solve.

If you listen to Radio National in Australia there was an interview today (9 Nov 25) with Professor Hannes Leroy – director of the Erasmus Centre for Leadership in Rotterdam - who talks about the ‘lost art of daydreaming’.

He studies the way the mind wanders and how that has positive impacts on creativity and problem solving.

It seems when the mind is let free to wander it can filter through the ‘unresolved’ incidents, ideas and ‘stuff’ we carry around with us.

Being in nature creates opportunities for the mind to wander freely and, if it does it long enough, it can start to find solutions, make connections and associations that may lead to complex problems being solved.

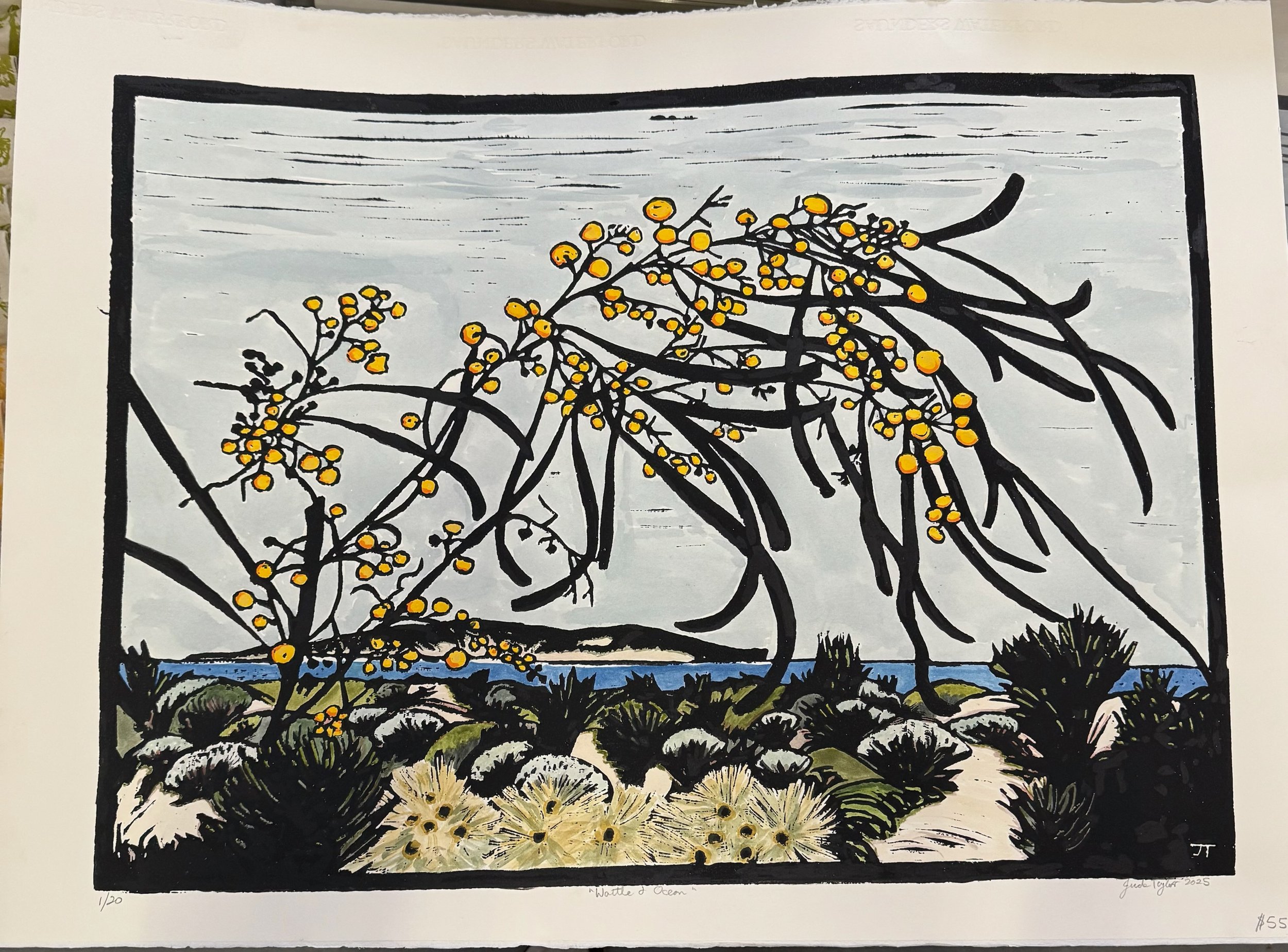

Look at these – would they capture your attention?

Would your attention wander from wildflower to wildflower feeling the effect of the aesthetic beauty?

Would they enable a lightening of the mental load carried on whatever you might have been working on until that moment?

2. Being Away – being away from the habitual stressors, experiencing unfamiliar surroundings and different stimuli can be restorative.

We get used to a certain daily experience and when we change this, especially in nature, it can help our brain relax and reset.

We don’t spend enough time in nature, so most natural settings are unfamiliar to us.

Even looking at a pot plant, a nature video, or an image of a lake and sunset on a wall can have some effect.

Professor Leroy talked about the art of retreating.

Taking ourselves away from the centre of activity, taking a step back to reassess, in effect, taking our eyes off the ball, not paying attention to anything in particular, but letting the mind be distracted by everything in general – so it can be unfettered to reassess, reconsider, reset and restore.

3. Extent – the scope or range of the experience affects the impact – there is going to be more awe and immersion if the experience in a multi-day walk through remote wilderness full of visual vastness and richness, or if it is a few hours in a nearby park where there are lots of trees and birds but you can still hear the traffic.

Both are useful and beneficial; both are restorative, but there is a huge reset and restorative impact of prolonged time immersed in nature where you start to feel at one with the environment.

Where there is no end in sight to the freedom to wander.

4. Compatibility – each individual has an affinity and motivation to be in nature and be impacted by it.

how much does the person want to be exposed to nature?

How much motivation do they intrinsically have to appreciate the time away?

As biophilic beings we are drawn to the natural fascinations we encounter in nature.

We ‘know’ it feels good to walk through a forest.

We ‘know’ it clears our head to go for a beach walk.

We ‘know’ taking time out is important to get perspective.

However, increasingly research is showing us that it’s this combination of 4 factors - often present when we take ourselves to pristine and natural environments - that lead to “involuntary” or “indirect attention” allowing our brains and their creative and problem solving functions, among others, to be restored.

Fan, J., B. D. McCandliss, T. Sommer, A. Raz, and M. I. Posner. 2002. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience14:340–47. doi:10.1162/089892902317361886.

Kaplan, S. 1995. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology 15:169–82. doi:10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2.

Leroy, H., Rofcanin, Y., Ogbonnaya, C., Benischke, M. H., & Fainshmidt, S. (2025). The Devil is in the Details: Zooming out in Leadership Research. Journal of Management Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.70013

Staats, H. 2012. Restorative environments. In The Oxford handbook of environmental and conservation psychology, ed. S. Clayton, 445–58. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.Natural environments have been consistently found to be conducive to creative performance.